Back to differentiation by modality. Whether we believe there is such as thing as learning styles is really a moot point. There are several good reasons to differentiate this way regardless.

Reason #1: Novelty

If a stimulus has any chance of becoming a memory, you have to pay attention to it. Novelty is possibly the best way to gain attention. We have all experienced driving to work on autopilot, arriving at school with no recollection of the 30 minutes that got us there. This can go on daily—until someone puts up a new billboard. “Hey! That’s new,” you think to yourself.

The same principle applies in the classroom. If every part of every day is pretty much like the one before it, your students are apt to go on autopilot, some more often and for longer periods than others, lowering the likelihood of creating a memory of your instruction.

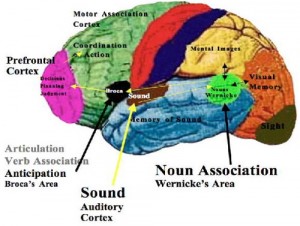

Reason #2: The brain stores information in multiple areas.

We’re all familiar with the generalization that left-brained people are logical and systematic while right-brained folks are creative and artsy. Our cognitive quirks and aptitudes go well beyond which hemisphere dominates.

Consider encoding and decoding of words in early grades. Many reading specialists recommend having students spell words by saying the letters while “writing” them with their fingers across a piece of sandpaper or a carpet swatch. Does this work? I don’t know; I work mostly with adults, many of whom know how to read already. If it does, its efficacy would seem to be predicated on the fact that one area in the brain recognizes tactile sensations while another processes auditory stimuli while another comprehends language and so on. The student is storing the memory of the way a particular word is spelled all over the brain.

It may be useful to think of the brain as a house and whatever you teach as a lint roller.

Trust me. You’re gonna love this analogy.

I have two dogs and two cats. Nary a day goes by that I don’t need a lint roller. I used to keep one in my night stand. Some mornings, while I was putting my coffee cup in the sink, one of the cats would rub against my leg. If I was running late, I didn’t want to run all the way back to my room to get the lint roller, so I got another one and put it in the junk drawer in the kitchen. Of course, then I’d get in my car and arrive at the office covered in dog fur. I began keeping another lint roller in my glove compartment and one in my desk at the office. I’m covered. More accurately, I am NOT covered—in animal fur—because I’ve got lint rollers wherever I might need them.

The more places your students can store their memories, the more likely they are to be able to retrieve them when needed.

So now you know the why. Tomorrow, we’ll talk about how.